Franklin is full of history. Even if you’ve lived here your whole life, you may not know these 10 interesting facts.

1. Franklin was almost called Marthasville, and it used to be in North Carolina

When the land that would become Williamson County and Franklin was officially ceded to the United States by the Cherokees and Chickasaws in 1785 and 1786, Fort Nashborough and a spattering of smaller fort-like settlements made up the bulk of the non-native population. The land, which was part of North Carolina, had been first settled in a bend on the western bank of the Cumberland River with the founding of Fort Nashborough in February, 1780.

Over the next 20 years, settlers increased from a few hundred to a few thousand. Land was cheap, and there was much of it for sale by various speculators and companies. It was also wild and dangerous. Tennessee was broken off by North Carolina in 1790 and given to federal government as the Southwest Territory, before gaining statehood in 1796. Three years later, in the third session ever of the Tennessee General Assembly, the state broke off from Davidson County to form Williamson County on October 26, 1799, as the state’s 16th county.

On the same day, the Assembly also passed an act to establish a town about 20 miles south of what had become the growing town of Nashville, which by 1800 had 345 residents, including 136 African American slaves and 14 free blacks.

Abram Maury had bought 640-acres of land from a Major Anthony Sharp in a bend of the Harpeth River, and he had the idea of erecting a town on it. (After the Revolutionary War, cash poor but land rich, many colonies paid off their debts owed in wages to soldiers with land grants.) Only one settler, Ewen Cameron, a 30-year old Scotsman from Virginia, currently lived on the land, in a log home on what is now Second Avenue South.

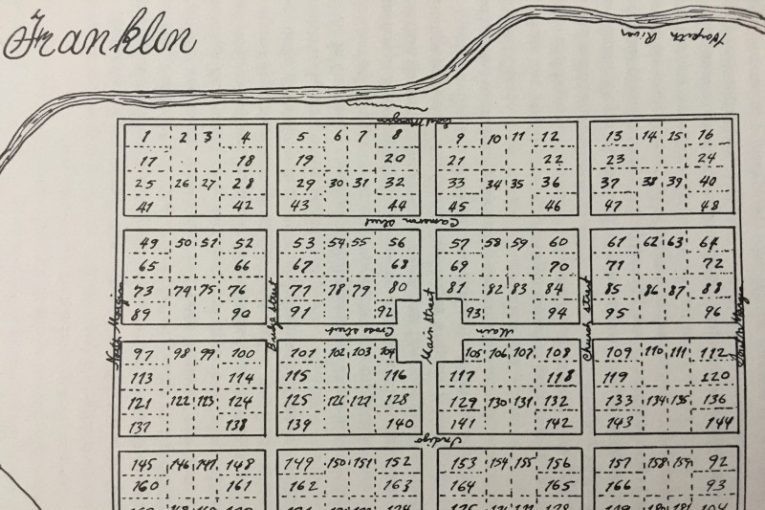

Maury (1766-1825) came to this area from Virginia in 1797. In 1798, he drew out a plan for a town named Marthasville, after his wife, on 109 of his acres. The plan can be seen above. Maury, who became a prosperous planter, surveyor and state senator, donated the lands for a public square, streets, and a Methodist Church.

However, Martha, perhaps less enthusiastic about the town’s prospects, demurred. As his second choice, Maury decided to dub the town Franklin, after Benjamin Franklin.

The plan he drew still, more or less, stands today. There were 16 square blocks, five streets each running north-south and east-west, a public square in the center, and 12 half-acre lots on a block.

The street names, also, were the same– except for the numbered avenues. They were East and West Margin Streets, Indigo Street and Cameron Street.

He began selling lots at $10 each. About a quarter of the 192 lots sold by 1800.

By 1806 he had helped build the historic courthouse still standing in the square today, as the seat of the county.

By 1813 the city would have nearly 1,500 residents and be growing quickly as a regional hub of commerce and agriculture.

2. Franklin’s First Food Truck Rolled Into Town in the ’20s

Food trucks might seem like a strictly modern innovation. Well, Franklin’s first mobile food business wheeled into town nearly 100 years ago.

Chapman’s Pie Wagon, which was run by Franklin resident Jim Chapman from 1922 to 1946, set up and sold hamburgers and fresh pies to hungry lawyers, townspeople and farmers right on the square.

The converted wagon, with its steel wheels and portable stairs, was a popular meeting place for coffee, lunch, supper or snacks after movies at The Franklin Theatre.

Inside, Chapman set up a kitchen with a serving bar at one end, and wooden stools and counters underneath bare light bulbs in the dining area.

Of course, pies were a specialty.

In the early ’40s, Chapman sold the wagon, and it became Mrs. Smithwick’s Pie Wagon.

In 1946, the wagon finally closed up shop and rolled out of town.

In 2011, Gwen and Dan Perkins renovated a historic trolley to look nearly identical to the original wagon. Friends order through the window at Chapman’s II, just like the original. The Perkins sold the business to Scot and Becky Keliher, who began operating the food truck in late 2014. In 2017, the Chapman’s II food truck was for sale.

3. Franklin’s Famous Flour Factory

Today you might just know them as those ugly gray things at the end of Main Street. But the grain silos south of Main Street and First Avenue South are the last reminder of what was Franklin’s largest industry for nearly a century.

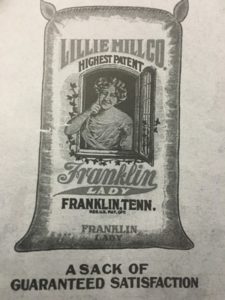

Joshua B. Lille established the Franklin Flouring Mill on the site in 1869. From there, it was sold to C.H. Corn and W.F. Eakin in 1909. In 1924, grain valued at $400,000 was used to produce over 70,000 barrels of “Franklin Lady Flour” and other products, which were distributed primarily in the southern market.

At its peak, more than 300 railcars of Franklin Lady Flour shipped from here each year in the early to mid 20th century.

At its peak, more than 300 railcars of Franklin Lady Flour shipped from here each year in the early to mid 20th century.

By 1926, several improvements were made including the construction of large concrete grain elevators at a cost of $60,000 with a storage capacity of over 250,000 bushels of grain making it the second largest such facility in the state.

Dudley Casey purchased the mill in 1945 from Ernest and Wilbur Corn.

The adjacent five-story mill built around 1887 and valued at $700,000 burned on January 8, 1958.

The grain elevators survived the fire and continued to operate for three decades.

4. Honky Tonks Used to Cover Franklin Road

Sure, Cool Springs and downtown Franklin are the places to go for Friday night drinks in Williamson County. Nowadays, anyway.

But for a good many decades of the early 20th century a string of roadhouses, juke joints and speakeasies filled the nights along Franklin Road with music, laughter and, of course, hooch.

From the late ’20s to the early ’60s and a bit beyond, if you had a thirst for dancing, drinking, dining or even a little gambling, the 16 odd establishments of varying repute along the stretch between Franklin and Brentwood would gladly quench it for you.

Prohibition ended when the Volstead Act was repealed in 1933, but states and counties could opt in or choose to remain dry. Williamson County went wet, but Davidson County- with the exception of the Nashville city limits- stayed dry as a bone.

It was in this atmosphere that these roadhouses sprouted up.

“Jackson Highway, which opened in 1929 and is now Franklin Road, and this series of beer joints- roadhouses- opened up along the way,” said Rick Warwick, historian for the Heritage Foundation of Franklin and Williamson County. “They were pretty notorious- there were roadhouse gamblers, and it was illegal to serve alcohol at the time here, but if you paid off the sheriff you could get away with it.”

Only echoes and shadows are left of most, a scattering of stones that flash past the car window on your way to work or play.

But one is still standing. It sits about halfway between the two towns, a little turnabout cut into the woods that frame it.

Today the building is home to the Franklin Road Animal Hospital at 1434 Franklin Road. But in 1929, until sometime in the ’60s, it was the called The Rendezvous.

The once toll house became a popular road house. In the 1920’s it was known as The Silver Moon and in 1934 it changed hands and the name was changed to The Rendezvous which it kept til the 1960’s. It was then bought by a group of businessmen one of which was Eddy Arnold. In the early 1970’s it was the office for the Brentwood Water Company, Charlie Mosely’s real estate and accounting office, and a businessman named Jack Corn. There are still some old asbestos pipes on the property that belonged to the Brentwood Water Company. As mentioned before, northern Williamson County was very dry and would not support development until water was made available.

Originally, in the late 1800s, the building was erected as a toll house. In the 1920s it became The Silver Moon and later The Rendezvous.

“The building was known to have the best dance floor on the strip which was verified by a long-time client,” Dr. Mark Ingram, the veterinarian at the Animal Hospital, wrote on their site:

“One of my early clients when I first opened the clinic had been the attorney for the owner of the nightclub. He told me that the sheriff was out here most every weekend. Several have told me that there was gambling downstairs. We recently had a visitor stop in and tell about a man from the Chicago area that brought in roulette wheels on a regular basis. He described a shoot out one weekend in which four patrons were killed. The attorney told me that he came in one day and the parking lot was full of cars but there were only two people sitting in a corner drinking beer. He told the bartender to go downstairs and get the owner and have him send a number of people back upstairs. He asked how could he defend him in court if it was so obvious that the main activity was gambling downstairs. For years after opening the clinic around 5:00 p.m. we would have working gentlemen burst through the door, look startled, say nothing, then turn around with a disappointed look on their face and leave.”

The owner-operator, John Clements, built it in and lived in the basement with his wife. They were even eventually able to get a permit to legally serve beer.

To help skirt the law, a lot of these types of places would just sell set-ups, as they are called. In other words, they’ll give you a glass of Coca-Cola, but bring your own Jack.

The Franklin Road(houses) list:

The Crossroads, also known at one time as the Cool Goose, was at the corner of Wilson Pike Circle and Old Hickory Boulevard.

The Wagon Wheel- later became the Brentwood Cafe, where First American Bank used to be.

The Palms- was one of the nicer dance places and had live bands. It was originally a Texaco station whose building was expanded to house a restaurant and a dance floor. It was where the Exxon station is now in center Brentwood.

The Stork Club- was one of the classier places, it charged a cover and had bands in the summer, with dining and dancing on a patio under an awning. Bartenders wore coats and ties.

The Gingerbread House- opened as a dinner club and later became a hot spot known as the Ship Ahoy during and after World War II.

The Rendezvous- was known for its hardwood dance floors and family-like atmosphere during its early years.

The Owl Club- was across the street from the Rendezvous, it burned down after the war. Gambling and dancing were equally popular here.

The White Way Inn- was located near the present site of Sew What Gifts and Stitches, This was a tough joint, as the contemporary saying went “The White Way Inn, the bloody way out.”

The Lucky Strike- was located near where Holly Tree Gap Road hits Franklin Road

Patton’s Place- was near the old Moore’s Lane and what is now Publix.

The Del Rio- is still standing as the first house on the right turning onto Moore’s Lane from Franklin Road.

“We took the wing that was the dance hall and made it our home,” Sue Owen told the Harpeth Herald in 1978. “My kitchen is where the bandstand was located.” According the Harpeth Herald, the Owns tore down the other wing of the club, which held the bar, dining area and restrooms, for lumber to build a barn on the property.

Green Acres- was at the corner of Concord Road and Franklin Road; before the Green Acres it was the site of a toll booth.

The Nightengale- was located opposite the former site of Yearkin’s Antiques near Moore’s Lane. It was a popular hangout for teens from the late ’30s and early ’40s. (There was no age restriction in effect. Though, according to the Herald story, if youths who got a little too rowdy their parents would be told, and in certain cases the sheriff might stop by for a little heart-to-heart.)

The Greyhound- is now the present site of the white colonial mansion on the west side of the road about three miles north of Franklin.

The New Deal Cafe- was across the street from the now-closed Jamison plant.

The River View- was later renamed the Blue Moon, and was located on the south bank of the Harpeth along Franklin Road.

5. The First Woman Sentenced to the Electric Chair

Franklin holds the dubious distinction of the home of the first woman sentenced to die by electrocution in Tennessee.

Her name was Betty Burge. She ran a boarding house on what is now Fowlkes Street just up the street from the Carter House. Burge, with her son Sherman, planned and perpetrated the murder of Rosa Mary Dean, a lone, young woman who was from out of town and down on her luck, in December 1949. If the stories of witnesses in the Burge’s trial in early 1950 are true, Burge killed more than once.

Dean was found on the cold morning of Dec. 12, 1949, behind the old Franklin High School gym on West Fowlkes Street with her throat slashed. She was nearly decapitated.

A virtual stranger, who came to town from Indianapolis looking for a place to stay, Dean’s murder– and the apprehension and trial of her killers— rocked Franklin and brought national attention to the crime.

Indianapolis looking for a place to stay, Dean’s murder– and the apprehension and trial of her killers— rocked Franklin and brought national attention to the crime.

Betty and Sherman were the only people she knew in town, from boarding at their house five years before. What Dean saw– or said she saw– then would lead to her death.

After arriving off the train late on Dec. 11, Dean went looking for a room at the Burges’s boarding house. Penniless and desperate, she threatened blackmail by saying she saw Betty help murder her lover’s wife, five years earlier. Supposedly, Burge murdered Sally Golden to marry her husband, John, so the pair could collect the life insurance money on Sally Golden. Rosa Mary Dean claimed she witnessed the murder and demanded money to keep quiet.

Betty and Sherman kept her quiet, all right, a silence Dean paid for in blood. The two beat her and cut her throat, before sneaking out in the early hours, with help from one of their boarders, to dump her body by the incinerator behind the old Franklin High School gym. A pair of students found her the next morning.

The Burges were soon arrested and a sensational trial ensued. Bobby Woodard, the accomplice, talked and testified. An incensed and curious public showed up to witness the trial and the killers. Newspaper accounts at the time estimate that 15,000 people crowded the square and streets by the courthouse in downtown Franklin for the two-week January trial.

In the end, both found guilty, Betty became the first-ever woman sentenced to die by the electric chair in Tennessee. Sherman also was sentenced to death.

In the end, both escaped the electric chair. Then-Gov. Gordon Browning commuted their sentences to 99 years.

Dean was buried quietly a week after her death in an unmarked grave, with police as pallbearers and no family present, or even known of, to send her off. In town, she was known only, and then just barely, by her killers.

6. Franklin was a Distiller’s Paradise

The area around Williamson County has always been known for its private stills. That seems to be a given in any place with both grain, a rural or mountain setting and, of course, men and women who like spirits.

From Leiper’s Fork Distillery, one of the first to open in more than 100 years of state and federal prohibition on distilling spirits:

Middle Tennessee has a rich but nearly forgotten history of whiskey distilling. In 1799, John Overton, serving as Supervisor of the Internal Revenue for the District of Tennessee, performed a general accounting of stills and found that there were 61 stills servicing the 4,000 inhabitants of Davidson County. As land began to open up to the south and west, many of these people began to settle along the Harpeth River Valley in the newly formed Williamson County. Many of these early residents to our county naturally brought their stills with them as they moved. In this early period of our county’s history, whiskey production was small in scale and conducted by individuals. As part of a farming operation, and true to their cultural traditions, many farmers fermented and distilled their excess grains in the form of whiskey. In those days, whiskey was used not only as a libation but also for medicines, disinfectants, an ingredient in perfumes and even as a currency for bartering.

By the mid 1800s, small commercial distilleries began to dot the landscape. In our area, the Boyd family operated a grist mill on the West Harpeth River and a distillery at the head of Still House Hollow. Colonel Henry Hunter, who originally owned the property where Leiper’s Fork Distillery resides, operated a small distillery on Old Hwy 96, just outside the Village of Leiper’s Fork. In county records, this piece of property was called the “Distillery Tract”.

As time passed and the Industrial Revolution began to emerge, distilleries became more technologically advanced, slightly larger in size and fewer in number. In 1886, the Nashville Union reported that the distilling industry was the largest manufacturing industry in the state. By the turn of the 20th century, Williamson County followed this trend, having only one legal distillery which made approximately 150 gallons of spirit per day. This was the J.H. Womack & Bro. White Maple Distillery. The White Maple Distillery was owned and operated by John H. and Towns P. Womack. Both brothers were born in Lynchburg, Tennessee in the 1860s. The Womack’s operated a grist mill in Lynchburg and were contemporaries of the Tolley, Motlow and Daniel families in Lynchburg. It was from these prominent distilling families that they learned the distilling craft. According to the federal census, by 1900 the brothers had moved to Franklin.

On this census their occupation was listed as “Saloon Keepers”. The White Maple Distillery began operation in May of 1901. The distillery produced two barrels of whiskey per day until they were forced to close in 1910. White Maple Tennessee Whiskey was distributed extensively throughout Tennessee and Northern Alabama. History and time, however, were not on the brothers’ side. The distillery only operated for 9 years, closing when Tennessee enacted its own statewide Prohibition in 1910. An article on the front page of the Tennessean newspaper, dated December 31, 1909, reads, “Distilleries and Breweries Must Close Tonight”. At midnight on this date, 41 distilleries shut their doors across the state. Many Tennessee distillers ran their last batches right up until midnight. With the stroke of a pen, Tennessee’s 100 years old legal whiskey industry was wiped away. Many distillers moved their operations to Kentucky, but, in 1920, when federal Prohibition was instituted by the Volstead Act, they too were forced to shut their doors.

Prohibition was not the end of the whiskey industry in Williamson County. Illegal or untaxed whiskey production had always been prevalent in the hills and hollows of our county and, with the implementation of prohibition, increased dramatically. It has been said by local old-timers that every spring in the county had an illegal still on it at one time or another. The natural limestone-filtered spring water in our area, which is inherent to the famous whiskey making regions of Scotland, Ireland, Kentucky and Tennessee, produced some of the finest illegal whiskey in the country. The infamous Williamson County Whiskey Ring shipped their local moonshine from this area to city centers such as Nashville, Cincinnati and Chicago. Sam Locke was a revenuer in Williamson County during the Prohibition era. On Saturday, March 7, 1925, as he unlocked the gate to his family farm, he was gunned down by hired henchmen of the Williamson County Whiskey Ring. He had done his job a little too well, and in the course of a 3-month time-frame had busted more than 73 illegal whiskey stills in the county. This brazen act shows the deadly seriousness with which these illegal distillers guarded their profits and livelihoods.

7. Franklin’s Current Shape Came from a Battle with Brentwood

In the 1960s, plans were announced for the building of Interstate 65, cutting straight through Franklin. Long-planned construction on Highway 96 was beginning. As Nashville grew, so would its suburbs. Change and growth were on the way.

What began with the modern expansion of Williamson County in the ’60s continues yet today. The first boom began to take shape as the ’60s ended. A battle for land between Brentwood and Franklin would erupt out of that growth, and create the jagged city limits that exist between the two today.

In March 1969 when Brentwood voted to become an incorporated city, 4,000 people lived there. It would increase 500 percent by 1990, with nearly 20,000 people. Franklin, in 1960 had about 7,000 residents. By 1990 it had 20,000 people. In 1970, there were 54 subdivisions under construction in the county. The extension of Interstate 65, which reached Franklin by 1970, had almost everything to do with it. So did a coming mall, which in the ’70s was just a twinkle in the eye of developers. Land that in 1969 cost $2,000 per acre suddenly cost $10,000 and more, as commercial developers competed to get in on the commerce that the highway would bring.

Thus a previously quiet rural area populated by vast tracts of farms began to become Cool Springs.

Franklin and Brentwood both competed to get in on the tax revenue that would come out of it.

In the early 1980s, all of what is now Cool Springs sat in unincorporated land between Franklin and Brentwood. The process that would create not the CoolSprings Galleria, and in effect Cool Springs itself, started with a simple land grab.

Led by mayor Tom Nelms, Brentwood annexed land south of Moores Lane in the early ’80s.

Franklin’s mayor was six-time incumbent Jeff Bethurum. He had just greenlit a major bypass called Mack Hatcher Parkway. He called Brentwood’s action a “violation of their promise,” that Brentwood leaders had made to Franklin about where their future limits lay. Helms felt that the no-man’s land of Cool Springs between the cities should remain with the county. This set off an annexation escalation that shaped both the cities and their futures.

Betherum moved to annex 2,200 acres in the no-man’s land between the cities, which Nelms pleaded with the Board of Mayor and Aldermen not to approve. They did, over his hearty exhortations. By 1987, Franklin would add 7,000 acres, nearly doubling the size of the city’s limits. Critics, like Helms, claimed Betherum had a developer in his back-pocket.

The largest single annexation was 4,500 acres east of the interstate.

“Not only did we have to stop Brentwood, we also were receiving a lot of controversy for putting in too many apartments in Franklin,” Betherum said later on to a newspaper interviewer. “My idea was to annex land way out there, and put the apartments on the land, out of sight, out of mind.”

One annexed property belonged to a farmer named Marvin Pratt, who owned a 220-acre farm in the Mallory Valley area, just west of Interstate 65. In 1985, Pratt settled on the notion to sell his land, which he bought for $40,000 in 1954 with a $5,000 down payment, to a developer.

He was approached by Southeast Ventures, led by George Volkert, who had helped build two Nashville malls: Hickory Hollow and Rivergate.

“The idea of a Williamson County mall was tantalizing,” wrote Robert Holladay in Franklin: Tennessee’s Handsomest Town. “All the local sales tax would remain in the county; property-tax coffers would be full. Williamson County shoppers would not have to go to Nashville to spend their money.”

Of course, the Galleria Mall would eventually open in August 1991, and truly kick growth into another level that has hardly cooled in the intervening 25 years.

8. The Biggest Blockbuster That Never Happened Filmed In Franklin

In 1906, a Nashville historian and novelist named John Trotwood Moore wrote a book that culminated with a scene from the Battle of Franklin.

It was a bit of a dime-store novel, with gory scenes and melodramatic chivalry, but a good story, which became very popular. The Bishop of Cottontown, as it was called, caught the eye of several studio executives in burgeoning Hollywoodland, California.

The story rang reminiscent of the book (The Clansmen) that the first true blockbuster “Birth of a Nation” had been based on in 1915. A rival studio hoped to copy the success of ‘Nation’ with Moore’s story.

Metro Film Studio, the forerunner of MGM, sent director Allen Holubar and thousands of cast members to Franklin to recreate the battle and film it – an on-location filming that was unorthodox for the time.

Metro Film Studio, the forerunner of MGM, sent director Allen Holubar and thousands of cast members to Franklin to recreate the battle and film it – an on-location filming that was unorthodox for the time.

Dubbed “The Human Mill”, it soon turned into a disaster.

For starters, once the cast and crew arrived, they realized that the field, where the battle had taken place, had been built on and developed too much for them to shoot realistic Civil War scenes. Telephone wires inconveniently would ruin many shots. However, the movie inched forward.

The blockbuster that never was ended in Hollywood, when back from the field of battle, Holubar had to stop filming because he caught Typhoid fever, ironically a disease many Civil War soldiers fell to. He died a few months later at 35. It was conjectured he contracted the illness from infected water in Franklin while filming.

Hoping to recoup what had been filmed for historical purposes, the Tennessee Civil War Commemoration Committee asked for it 1959. They were told it had burned in a fire.

9. Race Riot after the Civil War in Downtown Franklin

In the chaotic aftermath of the Civil War, in the early days of Reconstruction, with the local economy shattered and no clear path forward in this new dawn, tensions and embitterment reached new levels.

Once the backbone of southern economics, the plantation system had its back broken. Whites and newly freed blacks were universally not just out of work but no longer knew the rules of daily life. Or if there were any. The government was not yet reestablished or settled enough to create any real sense of law and order.

In this tinderbox, a spark lit in Franklin on July 18, 1868. Divisions were not starkly between black and white; there was also those who were politically Radical and Conservative. Radical Republicans had a very different idea about punitive reconstruction, while conservatives supported a more forgiving approach. Blacks and whites belonged to both factions.

The riot had its beginnings in the marching downtown of the local Colored League, made of armed ex-slaves and soldiers. They had been marching through town with drums and a fife. They were apparently accosted and shot upon in the afternoon. Tensions, already high, turned to violence and fear of violence.

Conservatives feared that the marching had a military aspect, and felt not quite sure of their safety from the marchers. In the afternoon, a Col. John House and some men approached a few members of the League. Harsh words were exchanged between him and a Mr. J.C. Bliss, one of the Colored League. House assaulted Bliss, who then went to other marchers asking for a pistol.

From there, things deteriorated quickly.

Men gathered at House’s store and took up arms. Meanwhile, the League marched out of town and regrouped. They gathered muskets and other arms, and decided to head back into town.

At half past eight, the League marched towards the public square and the party of Conservatives estimated at from 25 to 30, apparently under command of Col. House, formerly of the Rebel Army, took position under the corner of the wall of House’s store facing the square. A standoff ensued.

Telegraph wires were cut, and troops were called in from Nashville to quell the sides.

At least 7 people were injured in the riot, according to the Freedmen’s Bureau’s report made at the time.

From the report:

The Colored League had recently procured drums and a fife, and had been marching around about the outskirts of the town after supper for several nights without disturbing anyone. On different occasions they were interrupted by colored Conservatives (Dick Crutcher and A. J. Gadsey passing through their column while marching, firing shots). In consequence of this interference some members of the League consulted a lawyer and prominent citizens to ascertain if any legal steps could be taken to protect themselves against these disturbances. Finding that there was no legal remedy for these annoyances the League armed some of its members for protection.

They were again disturbed and fired on, and returned the fire without injury to anyone. The occurrence taking place out of town was perhaps not known to many citizens.

A general feeling of insecurity seemed to seize upon the members of the League and the idea prevailed that their procession and marching were objected to by many persons and fears were entertained that attempts might be made to prevent their continuances. There is no doubt that the Conservatives viewed the marching and displays of the League as a military demonstration and feared that it might result in strife. Impudent remarks and foolish boasts were made by individuals of both parties, and each had come to regard the other with a jealous eye.

On the 6th instant, there was a political meeting which was addressed by Mr. John Trimble and Mr. Elliott, Republican candidate for Congress & State Legislator respectively. This meeting passed off quietly and amicably. In the afternoon a colored Conservative named Joe Williams passed through the town and was prevailed upon to return and speak. After he had spoken a short time, the Radicals became dissatisfied with his style and attempted to withdraw from the meeting. A Mr. J. C. Bliss who was a member of the League, was assailed by Col. John House and a party of armed men who seemed to be acting under his orders. He was struck by this Col. House and assaulted by abusive epithets. Mr. Bliss then went among the members of the League in a very excited condition and attempted to get a pistol with which to defend himself or to attack Col. House.

This altercation between Bliss and House plus the efforts of the Conservatives to prevent the Radicals from leaving the meeting created great excitement among the members of the League.

They marched away from the point where the speaking occurred and fired a few shots in the air as they moved off as a salute, they claimed. Their white friends urged them to disperse and go to their homes, which they seemed unwilling to do, feeling that their liberties were infringed upon; however they were prevailed upon to march out of town to a grove where they were addressed for an hour and a half by Mr. Elliott & Mr. Clifton, both of whom again urged them to disperse and go home.

They seemed to object to this for two reasons – the first was that the Conservatives would attribute their retirement to cowardice; the second that they had planned a torchlight procession for the evening which they were unwilling to abandon, but they finally decided to march to the public square and there break ranks, dispersing to their homes, giving up the plan of a torchlight procession. This was about half past eight o’clock in the evening.

In the meantime, it was manifest that a collision was expected – and the Conservatives were preparing for it by gathering arms and ammunition into the store of Col. John House — and perhaps other places around the square. During the afternoon, the number of arms also seemed to have increased among the members of the Loyal League, numbering perhaps ten muskets and a few pistols, the number not known. At half past eight, the League marched towards the public square and the party of Conservatives estimated at from 25 to 30, apparently under command of Col. House, formerly of the Rebel Army, took position under a corner of the wall of House’s store facing the square.

10. The Interurban was Franklin’s First and Still Only Public Way to Nashville

Before I-65 made getting to Nashville a 30-minute drive from Franklin, the first major connection between the two cities was the Nashville-Franklin Interurban Railway.

In the late 19th century, the growing utilization of electricity led to more intercity travel from larger cities with streetcars and interurban railways. Streetcars first reached Nashville in 1889. In 1902, Franklin resident Henry Hunter Mayberry decided that his town needed a connection to Nashville. Two lines were built running north-south, the Nashville-Gallatin and what would become the Nashville-Franklin. A third line to Columbia was never be completed. The Nashville-Franklin line was an electrified rail line that gave an alternative to the unpaved roads and tollgates on Franklin Pike.

On Christmas Eve 1908, the line finally reached the Franklin Square. The first train arrived with two cars loaned by the Tennessee Central Railway, one being the TC’s president’s private car, The Cumberland. When the train arrived at 2:30, crowds cheered and whistles blew as a brass band played “Dixie”. Franklin mayor E.M. Perkins drove the golden spike. Judge Pollard, one of the leaders who helped to build the Interurban, declared at the ceremony “And someday, Franklin will reach out her strong arms and take in her chief suburb – the city of Nashville.”

Stations for the Interurban stopped at what is now Mallory Lane, Moores Lane, the Tennessee Baptist Children’s Home, Ashlawn, Murray Lane, and the corner of Franklin Road and Old Hickory Boulevard. The Franklin terminus was located on the Square.

The tracks traveled out 3rd Avenue, then turned towards Nashville on Bridge Street. Once crossing the river, the Interurban went around Harlinsdale Farm. While the path of the Interurban was close to Franklin Pike, it was not a parallel route. The Interurban’s route crossed Franklin Pike twice to find the most level route with the easiest gradient. The first crossing was just south of Mallory Station Road, in front of where the Vanderbilt Legends Club clubhouse currently stands. The tracks crossed Moores Lane at the current Mooreland Estates neighborhood.

Trains began running regularly in April of 1909. Passenger service began daily at 6 AM and trains left Franklin and Nashville every hour, on the hour. Cars ran until 11:30 at night, while an accommodation would be made for any riders who went to the theater in Nashville. No matter how late a show might run, the Interurban would wait for passengers with a ticket to the theater. While there were 20 listed stations along the line, passengers could flag down the train at any point along the line to board. Once on board, passengers could pull a brake cord, within a reasonable distance, to be let off at any point along the line.Tracks crossed Franklin Pike north of Calender Road, which is now Concord Road. One of the former Interurban stations, Hayesland, still stands in the Meadowlake subdivision across from the AT&T building in Brentwood. The former power station for the Interurban stood on what is now the Shell Station at Franklin Road and Old Hickory Boulevard. The tracks continued north towards the city limits, with a station in front of Franklin Road Academy, Kirkman, that is still standing today. The Nashville terminus was at Bransford Avenue and 8th Avenue South, where the line connected to the other Nashville streetcars.

Trains began running regularly in April of 1909. Passenger service began daily at 6 AM and trains left Franklin and Nashville every hour, on the hour. Cars ran until 11:30 at night, while an accommodation would be made for any riders who went to the theater in Nashville. No matter how late a show might run, the Interurban would wait for passengers with a ticket to the theater. While there were 20 listed stations along the line, passengers could flag down the train at any point along the line to board. Once on board, passengers could pull a brake cord, within a reasonable distance, to be let off at any point along the line.Tracks crossed Franklin Pike north of Calender Road, which is now Concord Road. One of the former Interurban stations, Hayesland, still stands in the Meadowlake subdivision across from the AT&T building in Brentwood. The former power station for the Interurban stood on what is now the Shell Station at Franklin Road and Old Hickory Boulevard. The tracks continued north towards the city limits, with a station in front of Franklin Road Academy, Kirkman, that is still standing today. The Nashville terminus was at Bransford Avenue and 8th Avenue South, where the line connected to the other Nashville streetcars.

Opposition to The Interurban

As with many big projects, the Nashville-Franklin Interurban would not be met without some opposition. The opposition was fourfold and included merchants in Franklin and Brentwood, the owners of large estates in Williamson County, the Louisville & Nashville railroad, and the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Merchants believed that the Interurban would hurt their business by allowing customers to travel easily to Nashville, which would be proven true. The L&N’s passenger service to Franklin would never be the same after the opening of the Interurban. The ladies of the UDC’s biggest complaint with the Interurban was that the tracks that circled the Confederate Monument were financed by a Northern bank. The owners of the Interurban would appeal to these ladies by offering them a free ride to the Hermitage.

The Interurban reached its peak in the mid 1920’s. Commuters to Nashville, students at Robertson Academy and Nashville colleges, and shoppers alike all took the Interurban into the capital city. From 1909-1926, ridership averaged 30,000 riders per month. After road improvements and paving between Nashville and Franklin, average ridership dropped by 10,000 per month. However, the Interurban never lost money. Beyond passenger service, the line also carried freight traffic. Center-cab electric locomotives hauled anything and everything from logs to livestock to bootleg liquor.The greatest opposition faced came from some of the larger estate owners, in particular James Caldwell. Caldwell’s estate was just south of Thompson Lane, near the site of modern day Caldwell Lane. Caldwell was vehemently opposed to the Franklin Interurban, which ran right through his property. Both wealthy and influential, Caldwell had previously challenged and been successful in keeping commercial development off of Franklin Road, which is why there is still no commercial development along Franklin Road north of Brentwood until you reach Melrose. Caldwell sued the Interurban, who then countersued Caldwell for condemnation. The case reached the Tennessee Supreme Court, who found in favor of the Interurban and allowed them to build across Caldwell’s land. However, the court humored Caldwell and made his driveway a public road, which required the Interurban to stop and have a conductor block the road while the train crossed. While the stop came to the chagrin of operators and passengers alike, the operators would have the last laugh, as they began to blow their whistle at the crossing every time they passed by.

Check out a video of the Interurban here.

The End of The Interurban

While it has been 75 years since the sparks of the electric wiring and the squeal of metal wheels on rails interrupted the calm of Franklin’s Square, the Nashville-Franklin Interurban could give precedence for intercity commuter rail from Williamson County to Nashville. Even though there are no immediate plans to bring commuter trains south, the continued growth of the area might show regional planners the necessity for more public transportation. Luckily, these planners can look ahead by looking back at the success of the Nashville-Franklin Interurban line.In 1941, Nashville began replacing some of their streetcars with buses. Since the Nashville-Franklin Interurban used the same rails in the Nashville city limits, they would soon follow suit. Though the original interurban cars had been replaced in the 1920’s, the newer cars were replaced by buses. The final run of the interurban cars was on November 9, 1941. Freight service continued until March 1943, when the line would be abandoned. The rails would be removed and the metal would be donated to the war effort. The buses offered two routes from Franklin, one up Hillsboro Road through Grassland and one up Franklin Pike through Brentwood. The buses continued their operation into the 1960’s before ceasing as well.

Thanks for sharing this awesome history!