By GREGORY L. WADE

Williamson County’s history is replete with remarkable coincidences and personalities.

One such story of fate surrounds Tennessee’s George Jordan and New England’s Edward Hatch.

By late 1864, the Civil War in our county had reached its bloody peak.

On Nov. 30, the Franklin battle began about where today’s Target on Columbia Pike stands, with soldiers slogging across two miles of open plain before the battle reached its horrible apex on the ground around the Carter House. This carnage virtually gutted the Confederate Army of Tennessee.

However, its commander, John Bell Hood, attempted one more fight at Nashville, only to be routed on Dec. 15 and 16. After that mismatch, the Confederates found themselves battling for their lives on Dec. 17. The federals pursued the retreating Southerners back through Franklin to the West Harpeth River, near the Tollgate development in modern-day Thompson’s Station.

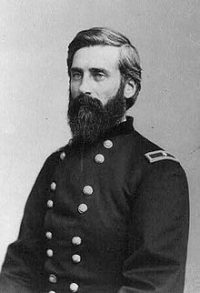

One of the federal cavalry commanders who enhanced his fighting reputation on that gloomy Saturday was Edward Hatch. Born in Bangor, Maine, he rose to the rank of brigadier general in early 1864 while serving with the Iowa cavalry under Ulysses Grant. As night fell along the swollen stream, Hatch’s troopers and the Confederate rear guard endured a savage fight. Union cavalry commander James Wilson reported, “Hatch’s division … made several beautiful charges, breaking the rebel infantry in all directions …” The fight at the West Harpeth, while brief, resulted in Medals of Honor for two federal officers, an indication of the battle’s intensity. When the war ended months later, Gen. Hatch stayed with the regular army, his path leading to a heroic soldier born in Williamson County.

Only about 15 miles east of the West Harpeth battlefield was the thriving community of Triune. The once-prosperous village lay just south of Nolensville along the Nolensville Pike and near the road to Murfreesboro. The area boasted several schools and churches and was known as one of the most fertile landscapes in Middle Tennessee. There was also a large slave population. Triune’s future was thought to rival that of Franklin until the Civil War, when most of the village was destroyed by federal troops.

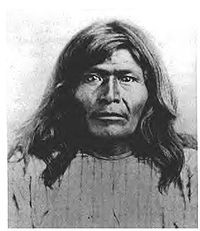

In the late 1840s, George Jordan was born into slavery in the Triune area. He would eventually escape his life of servitude to achieve fame in his own right. Like many soldiers or future soldiers in the years after the Civil War, George headed west. He likely aspired to leave the harsh politics of a rebuilding South as well as seeking opportunity in a part of the country perceived to offer a fresh start.

During this time, Native Americans, sometimes brushed aside during of the chaos of the Civil War, again became a priority for a U.S. government facing pressure from those seeking a new life west of the Mississippi. Prospects of fertile, cheap land with abundant water appealed to many white settlers while others sought instant riches in mineral strikes.

Often ignored were the Indian tribes who thought they should have a say so about who owned the land.

In 1866, George Jordan joined a federal cavalry regiment that would be instrumental in many of the campaigns against the Indians. Most of Jordan’s early life is unknown and Franklin’s Tina Callahan Jones, an authority on African American soldiers from Williamson County, believes “he may have been in Nashville,” helping to build the federal works. He enlisted in 1866, a year after the war ended.

It is not known whether George saw the irony as a former slave that he and others like him would be used in subjugating another race. Anyway, these eager troops would be called Buffalo Soldiers by the Indians. Some say the curly hair and dark skin of the buffalo reminded the Indians of men like George Jordan now crossing their lands.

These African American units would compile a long legacy of honorable service up until the Korean War.

By early 1880, an Apache chief, Ogima Victorio, had grown weary of appealing to federal officials for his people to live on tribal traditional lands instead of reservations. Consequently, he led a band of warriors to attacks on settlers in the New Mexico and Arizona territories. That spring, near Fort Tularosa in southwest New Mexico, Sgt. George Jordan and the U.S. 9th Cavalry were dispatched to protect settlers while establishing a supply depot. The Williamson County native, now a veteran noncommissioned officer, was met by a courier who informed him Victorio was set to attack. The messenger pleaded with Jordan “to save the women and children from a horrible fate.” Already exhausted from a long march, he and 25 troopers trudged to the fort but found no sign of the Apaches.

Hours later, however, they were attacked and were successful in repelling Victorio’s warriors. In one of those twists of fate, Jordan’s commander was none other than Edward Hatch, now serving as colonel of the 9th Cavalry in the U.S. Army of the post war era. Hatch arrived at the battlefield the next day unaware he was serving with another soldier who would eventually receive great recognition. Ten years later, Jordan received the Medal of Honor for his leadership at Tularosa. His 1890 citation in part says “… he (Jordan) stubbornly held his ground in an extremely exposed position and gallantly forced back a much superior number of the enemy …” As for Victorio and his band, they retreated across the border into Mexico, hunted down and killed by the Mexican military in late 1880.

It is not known if Jordan and Hatch were aware of their Middle Tennessee connection where Hatch led cavalry attacks at the West Harpeth while Jordan was growing into manhood at Triune and Nashville. Hatch passed away in 1889 in Fort Robinson, Nebraska, at the age of 59. He is buried at the Fort Leavenworth, Kan., National Military Cemetery, along with Indian fighter George Custer and Fitz Lee, another Buffalo Soldier Medal of Honor recipient. And as a side note, in another close connection with Franklin, Hatch followed Gen. Gordon Granger as commander of the Army’s Department of Arizona before the battle against Victorio. Granger was once the commander of Union forces in Franklin for which the preserved fort near Pinkerton Park is named.

George Jordan died in 1904 in his fifties and is interred at Fort McPherson, Neb., National Cemetery along with 66 other Buffalo Soldiers. He rests just yards away from another African American Medal of Honor recipient, Emanuel Stance, recognized for courage in an 1870 action against the Apache.

For more on George Jordan, CLICK HERE.

Please join our FREE Newsletter